Before we go deep: If you’re just looking for the quick formula, skip the theory and use our MBS Calculator. If you want to actually understand why MBS matters, how the math works, how lenses are made, and how they’re cut to fit a frame… keep reading.

Have you ever wondered how a round eyeglass lens blank becomes the precise shape of your frames? In the optical world, Minimum Blank Size (MBS), also known as Minimum Uncut Size, is the key concept that determines how big a lens blank needs to be before it’s cut to fit your frame. This article will explore what MBS means, why it’s important for both optical professionals and curious eyewear enthusiasts, and how lenses are made and cut to fit into frames. We’ll also touch on differences between single-vision and progressive lenses (and why MBS matters for both). By the end, you’ll appreciate the precision behind “how things are made” in the eyewear industry, and why a simple number like MBS is critical for comfort, appearance, and optical quality.

What Is Minimum Blank Size (MBS) or Minimum Uncut Size?

Minimum Blank Size (MBS), sometimes called minimum block size or minimum uncut lens size, is the smallest diameter a lens blank must have to be cut into a given frame shape. In other words, it’s the minimum size of the raw lens (usually a round disc) that will “cut out” to fill your eyeglass frame without leaving gaps. If a lens blank is any smaller than this size, it simply won’t cover the entire opening of the frame once it’s cut to shape.

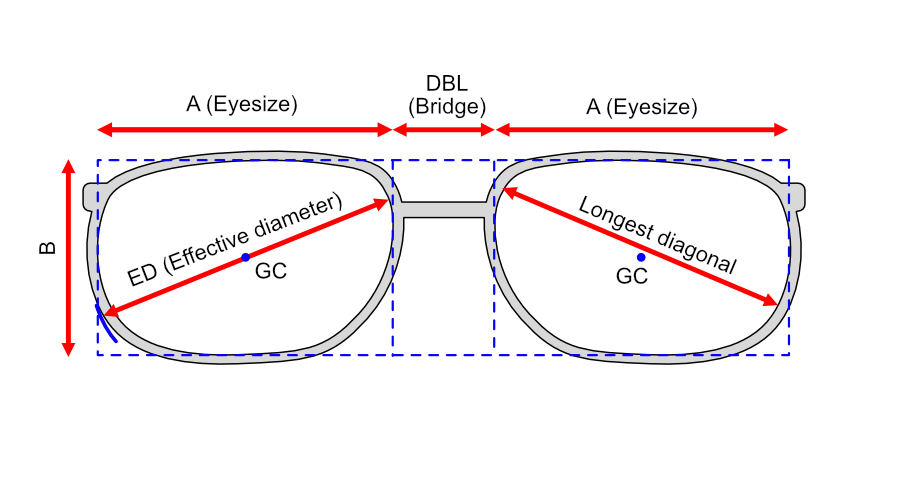

Every eyeglass frame has certain key measurements (using the boxing system in optics) that determine the required lens blank size. The main ones are:

- A (Eye Size): The horizontal width of the lens opening (in mm).

- B (Lens Height): The vertical height of the lens opening.

- DBL (Distance Between Lenses): Also called bridge width – the gap between the two lenses (essentially the bridge of the frame).

- ED (Effective Diameter): The longest distance across the lens shape. This is essentially twice the longest radius from the lens’s geometric center. The ED represents the diameter of the smallest circle that can completely enclose the lens shape. It’s a crucial number – if the optical center is centered in the frame, the ED alone is the smallest blank that could fit the lens.

- Frame PD (Geometric Center Distance or GCD): The distance between the geometric centers of the two frame openings, essentially A + DBL (the frame’s “pupil distance”).

Now, why does ED alone often not equal the required blank size? Because your pupils are rarely exactly at the frame’s geometric centers. For clear vision, lenses must be positioned (decentered) so that the optical center of each lens aligns with your pupil. This means the lens blank often has to be larger than the frame’s ED to accommodate shifting the lens optics left/right or up/down. The minimum blank size takes into account this decentration (the lens movement needed to align with your eyes) plus a small safety margin.

In formula terms: a simple rule for single-vision lenses is:

MBS=ED+(Frame PD−Patient PD)+2 mm

Here, (Frame PD – Patient PD) represents the total decentration needed (how much smaller or larger the patient’s pupillary distance is compared to the frame’s center distance), and the extra 2 mm is an allowance for edging and imperfections. Many opticians use a formula of MBS = ED + Total Decentration + 2 mm as a guideline for the smallest blank diameter that will work. The 2 mm margin ensures the lens cutter has a bit of wiggle room – accounting for any minor lens outline flaws (chips on the blank’s edge or slight misalignments) so that you don’t end up with a sliver of missing lens at the edge after cutting.

Example: Suppose your frame’s A = 52 mm, DBL = 18 mm, and the lens shape’s ED = 57 mm. The frame PD = 52+18 = 70 mm. If your distance PD (pupillary distance) is 62 mm, the total horizontal decentration needed is 70 – 62 = 8 mm (meaning the lenses must be inset 4 mm per eye to line up with your pupils). Plugging in: MBS = 57 + 8 + 2 = 67 mm. This tells the lab that a lens blank should be at least 67 mm in diameter to cut this prescription for that frame. A smaller blank would risk the “lens will not cut out” error – essentially, a too-small lens that can’t fill the frame opening.

Why Does Minimum Blank Size Matter?

Calculating the correct minimum blank size is crucial for technical, cosmetic, and cost reasons:

- Ensuring the Lens Fits the Frame: This is the most basic importance – if the blank is too small, the lens simply won’t cover the eye wire of the frame. Opticians and lab techs must ensure the chosen lens blank diameter is at least the MBS, otherwise they’ll end up with gaps at the edges or a lens that cannot be mounted. Modern edging machines will alert “lens will not cut out” if the blank is insufficient.

- Thinner, Lighter Lenses (Especially for Strong Prescriptions): Using the smallest possible blank for a given job helps minimize lens thickness. The bigger the lens blank (beyond what’s needed), the thicker and heavier the finished lens can become – particularly for higher-power lenses. Frame size and decentration directly affect thickness: A larger lens diameter means more material at the periphery, which for a plus-power lens dramatically increases center thickness and magnifying effect. For example, a +5.00 D hyperopic lens edged to a 60 mm diameter might have ~3 mm center thickness, but the same prescription in a 70 mm blank could end up around 7 mm thick in the center – over twice as thick, just from 10 mm larger blank! For minus (nearsighted) lenses, the thickest part is the edge; a larger blank doesn’t change the center thickness much, but it means you’re keeping more of the thick edges around. In practice, an overly large blank on a minus lens won’t increase the lens’s center thickness or weight as dramatically as it does for a plus lens (since you’ll cut off the excess thick edges), but it does increase edging time and can still lead to unnecessarily thick edges in the final glasses. In short, for plus lenses, keeping blank size just-large-enough is critical to avoid coke-bottle lenses. Even for minus lenses, using an appropriate blank size ensures you aren’t wasting material or time grinding away excess lens.

- Cosmetics and Optics: A lens that’s too large for the frame not only can be thicker – it might also cause more optical aberrations toward the edges or have more visible “bowls” for plus lenses. Thick edges on minus lenses can be unappealing and may affect how the lens sits in the frame. Also, if a lens is decentered a lot from the blank center, one edge of the lens will be thicker than the other. Minimizing that decentration by good frame selection or correct blank size can keep lens thickness distribution more even. Using the smallest effective blank helps maintain better optics by reducing how far from the optical center the finished lens extends.

- Weight and Comfort: Thicker lenses from oversized blanks are heavier. Especially with strong plus prescriptions, an extra millimeter of center thickness can add noticeable weight. Keeping the lens blank just large enough means the finished lenses will be lighter, which is more comfortable for the wearer.

- Cost and Availability: Lens blanks come in standard diameters (common stock sizes are around 60, 65, 70, 75 mm, etc., often in 5 mm increments ). If your calculated MBS is right on the edge, you might have to jump to the next available blank size. Larger blanks, especially in high-index or specialty lenses, can be more expensive. In some cases, if an off-the-shelf lens blank isn’t available in a needed large size, a lab might have to surface a custom lens (grinding a prescription onto a larger semi-finished blank), which can cost more and take longer. By knowing the MBS in advance, an optician can decide if a given frame is suitable for a patient’s prescription or if perhaps a slightly smaller frame would allow using a readily available stock lens blank. Using the minimum blank size optimizes cost and turnaround time – it helps determine if a stock uncut lens can be used or if a special-order blank is needed. No one wants to order an expensive 80 mm blank when a 65 mm would do; conversely, if the math says you need 80 mm, it’s better to know before trying to cut a 70 mm and wasting a lens.

- Waste Reduction: From the lab’s perspective, choosing the smallest possible blank for the job reduces waste. Any material cut away from the lens blank turns into plastic (or glass) shavings. Using an oversized blank means more waste and also more wear on cutting tools. That’s why labs stock multiple blank sizes and will pick the smallest that meets the MBS requirement. It’s both economical and environmentally smart not to grind away more lens material than necessary.

A good rule of thumb in eyewear dispensing is to choose a frame that suits the wearer’s PD – meaning the frame PD (A + DBL) shouldn’t be drastically larger than the person’s PD. “Select a frame whose PD is within about 6 mm of the patient’s PD” is often advised. This keeps decentration (and thus required blank size) reasonable, resulting in thinner lenses and a better look. When a small PD patient insists on a big fashion frame, or vice versa, MBS becomes a make-or-break calculation to ensure lenses can be made at all.

A good rule of thumb in eyewear dispensing is to choose a frame that suits the wearer’s PD – meaning the frame PD (A + DBL) shouldn’t be drastically larger than the person’s PD. “Select a frame whose PD is within about 6 mm of the patient’s PD” is often advised. This keeps decentration (and thus required blank size) reasonable, resulting in thinner lenses and a better look. When a small PD patient insists on a big fashion frame, or vice versa, MBS becomes a make-or-break calculation to ensure lenses can be made at all.

How a Lens Goes from Blank to Fit Your Frame (The Cutting Process)

To appreciate the importance of minimum blank size, it helps to understand how lenses are crafted and cut for your glasses. It’s a fascinating “how it’s made” process:

1. Lens Blanks: Most lenses start out as uncut blanks – typically circular pieces of optical material (plastic or glass) with a preset optical power. For single-vision lenses, a stock finished blank might already have the full prescription; for more complex prescriptions, labs use semi-finished blanks (with one side finished, and grind the other to the needed power). These blanks are usually around 65–75 mm in diameter (often ~70 mm). They look like flat or slightly curved discs – imagine a smooth hockey puck but transparent. If you’re using polycarbonate or high-index plastic, the blank might be thin at the edges and thicker in the middle for plus powers, etc. They may even have tint or coating on them already. Below you can see examples of round lens blanks prior to cutting.

2. Marking and Blocking: The optical lab technician next marks the lens blank with reference points. For single vision, they’ll mark the optical center (the point that should line up with the patient’s pupil). For progressive or multifocal blanks, they mark fitting cross, segment, or major reference points provided by laser markings or a layout chart. Once the blank is properly aligned for the patient’s PD and eye height, it’s time to block the lens. Blocking means attaching a sturdy holder (“block”) to the front of the lens blank with a special adhesive pad. The block usually has a pin or chuck that will fit into the edging machine. This step is crucial: the lens must be blocked at just the right spot so that when it’s cut, the optics align perfectly in the frame. If the lens needs to be decentered 5 mm nasally and 2 mm up relative to the frame’s geometric center, the block will be placed that exact 5 mm, 2 mm offset on the blank. That effectively recenters the cutting pattern on the blank to match where the pupil will be.

3. Tracing the Frame Shape: Meanwhile, the shape of your frame’s lens opening has been measured – either by tracing one of the demo lenses from the frame or from a digital file if the frame shape is in the system. This gives the edger machine a precise pattern to cut. In the old days, opticians used physical template patterns; today’s patternless edgers use a tracing arm or scanner to map the frame shape digitally. The key data from the tracing is the outline (2D shape) and the “effective diameter” of the shape – essentially the longest distance across it, which as we discussed dictates the minimum blank size when combined with decentration.

4. Edging (Cutting) the Lens: The blocked lens blank is placed into the edging machine. This machine is like a precise CNC grinder specifically for lenses. It knows the shape to cut (from the tracer data) and it knows how big the lens blank is and where the block is placed (hence where the optical center is relative to the shape). Modern edgers are computer-controlled marvels: many use diamond-coated grinding wheels to cut the lens while water sprays to prevent overheating. The machine will usually rough-cut the lens to a slightly oversized shape, then fine-cut it to exact shape and put a final edge finish. If it’s a metal or plastic full-frame, the edger will cut a V-bevel onto the lens edge so it fits securely in the frame groove. If it’s a rimless mount, the edger polishes the edge smooth and might even drill holes as needed. This whole process just takes a few minutes per lens – typically 3–7 minutes depending on material and complexity.

Throughout edging, having the correct blank size is crucial. The machine’s software often simulates the cut on the blank’s outline – if any part of the shape would fall outside the blank’s boundary, it warns the operator (this is the “won’t cut out” scenario). If the blank is only just big enough, the technician must align it perfectly when blocking. That 2 mm safety margin we add in MBS calculations helps here, providing a little buffer for slight mis-blocking or a chipped edge on the blank. During cutting, extra blank diameter also allows the lens to be held firmly by the edger’s chuck. If you tried to cut a lens on a blank that was exactly the shape size with no excess, you couldn’t safely clamp it without risk of the lens shifting or the machine’s clamps grinding the very edge.

5. Fitting the Lens into the Frame: After edging, the freshly cut lens is tested in the frame. The optician or technician checks that it “cuts out” properly – meaning it fills the lens opening all around without gaps, and usually that it’s not too large (sometimes a hair of sizing adjustment is needed for a perfect snug fit). The block is removed, and the lens is popped into the frame. If all calculations were correct, it fits precisely. If the blank was misjudged and a lens came out slightly too small (rare if MBS was followed), that lens is scrap. If the blank was much larger than needed, the lens will fit but one can tell from the overly thick edges or center that the blank was oversized – a missed opportunity to make it thinner.

Quality checks happen next, and then the process repeats for the other eye (with appropriate left/right decentration and likely a mirrored shape trace). Finally, both lenses are mounted and aligned. The result: a pair of glasses where the prescription is dead-centered in your visual line, and the lenses fill the frame beautifully.

It’s amazing to think that a few basic numbers (frame size, your PD, and lens shape) drive all those decisions. The minimum blank size calculation guides the lab from the moment they pick the lens blank off the shelf to the final edging on the machine. It’s truly the bridge between the design of your glasses and the manufacturing of your lenses.

Calculating MBS: Decentration, ED, and More (A Deeper Dive)

For those who love the technical side (opticians or the inquisitive DIY enthusiast), let’s break down the factors that go into calculating the Minimum Blank Size. As mentioned, the fundamental relationship is:

MBS ≈ Effective Diameter (ED) + 2 × Decentration (per lens) + 2 mm.

Let’s clarify each part:

- Effective Diameter (ED): This is the diameter of the smallest circle that can cover the lens shape. Think of it as the lens shape’s “worst-case width.” It’s typically the diagonal measure of the lens shape (since the longest dimension of an eyeglass lens is often at a tilt). If the lens were perfectly centered in the blank, the blank’s minimum diameter would be equal to the ED. For example, a round frame of 50 mm width has ED = 50 mm. A more rectangular frame 54 × 38 might have an ED around ~60 mm (stretching corner to corner).

- Decentration: This is how far the lens’s optical center must be moved from the frame’s geometric center. It can have horizontal and vertical components. Horizontal decentration per lens is usually (\text{Frame PD} - \text{Patient PD})/2 for each eye (using monocular PDs). If the patient’s PD is less than the frame PD, the lenses are decentered inward (nasally) – which is very common. For example, frame PD 70 mm vs patient PD 62 mm meant 4 mm inward decentration each lens in our earlier example. Vertical decentration (also called MRP height adjustment) is needed if the patient’s eye sits above or below the frame’s horizontal midline. For single-vision lenses, usually you center vertically if prescription isn’t strong; for multifocals, you have a segment height or fitting height that dictates vertical placement. Either way, if the lens needs to be moved up or down, that too effectively uses more blank in one direction. Most MBS formulas primarily consider horizontal decentration (since that’s often the bigger factor), but for progressives or lined bifocals, you must mind vertical placement as well.

- 2 mm Allowance: As noted, adding ~2 mm is a standard practice. This accounts for edges and ensures a bit of extra lens around the whole shape. Some formulas include it, some don’t explicitly – but in reality labs will choose a blank a few millimeters larger than the exact traced outline. Think of it like seam allowance in sewing.

Using the formula in a worked example for a single-vision lens:

Say we have Frame A = 60, DBL = 20 (so Frame PD = 80), ED = 63, and patient’s PD = 69. Frame PD (80) – PD (69) = 11 mm total decentration (meaning 5.5 mm per lens inward). MBS = 63 + 11 + 2 = 76 mm. The lab would likely select a 75 mm or 80 mm blank (whichever is immediately above 76 mm, since blanks come in set sizes). Indeed, lens blanks often come in 5-mm steps, so they’d use perhaps an 80 mm blank in this case. If we ignored MBS and grabbed a 70 mm blank, we’d be in trouble – the lens would almost certainly be too small after decentering.

One can also reverse-calc: if you know the blank size you have (say a stock lens only comes in 70 mm), you can figure out the maximum decentration/frame size that lens can handle. This is exactly what the MBS charts or templates do – by overlaying a frame shape on concentric circles of blank sizes and PD grids, they instantly tell you if, for instance, a 70 mm will cut out or if you need to surface a larger lens.

Monocular vs Binocular PD: It’s worth mentioning – for accuracy, especially with asymmetric PDs (one eye slightly farther from nose than the other), you calculate MBS per eye. In our discussion we’ve kept things simple assuming a symmetric PD. In practice, an optician will use the right and left monocular PDs. One eye might require slightly more decentration than the other, and thus a bigger blank. In a strict sense, you should pick the blank size to satisfy the larger of the two requirements (often the difference is small). For instance, using a formula for multifocals: MBS = ED + 2(decentration per eye) + 2*. If the right lens needs 69 mm and left 65 mm as in an example , you’d use at least a 69 mm blank for the right and could potentially use 65 mm for left – but practically, labs might use the same size blank for both, usually the larger, to keep things consistent.

Lens Shapes and Frame Tilt: It’s also interesting that the actual shape of the frame can affect the MBS. The simple formulas assume the longest radius from the lens center (that defines ED) is aligned horizontally (or vertically). But if the frame shape’s longest point is at an angle (like a cat-eye corner), and the decentration moves the lens in some direction, the true needed blank might be slightly more due to vector addition of horizontal + vertical offsets. In critical cases (e.g., big progressive lenses with lots of decentration), opticians will sometimes do a traced shape layout to double-check. This is essentially using software to simulate the lens on the blank. The formula is a great estimate and works for most jobs, but the “corners” of unusual shapes can sometimes drive the needed blank size. Optical labs account for this with cut-out checks and by often taking a trace of the frame and digitally positioning the lens before cutting.

The bottom line: MBS calculation ensures the right size lens blank is chosen from the start, preventing errors and optimizing the lens outcome.

Single-Vision vs. Progressive Lenses: Are They Different in MBS?

The concept of minimum blank size applies to all lenses, but there are a few special considerations with progressive addition lenses (PALs) and other multifocals:

- Progressive Lenses Require Larger Blanks: Progressive lens blanks are often made larger to accommodate the entire lens design (distance, corridor, and reading area). It’s not uncommon for PAL blanks to be 70–80 mm in diameter by default. This is because you typically cannot decenter the design too much; the reading “segment” area is usually inset ~2-3 mm from the distance reference point by design. If you have a narrow PD and a large frame, you might risk cutting off part of the reading zone. Manufacturers often specify a minimum fitting height for progressives (how small a frame’s B size can be before you lose reading area). Similarly, they could specify a minimum blank size for a given combination of PD and frame. In practice, calculating MBS for a PAL uses both horizontal decentration and vertical decentration (the fitting height relative to frame center) in a combined way. A more general formula for PALs is sometimes given as:

MBS = \text{ED} + 2 \sqrt{(Dec_H)^2 + (Dec_V)^2}

where Dec_H and Dec_V are the horizontal and vertical decentration distances. This essentially finds the true radial decentration distance. If vertical decentration is zero (optical center at frame midline), it reduces to the earlier formula. Many opticians don’t memorize this; instead, they ensure the frame is appropriate for the PAL by using manufacturer cut-out charts or software. The principle is the same though – more decentration in any direction means a bigger blank. - Inset for Near Vision: In bifocals and PALs, the near PD is smaller than distance PD (because your eyes converge when reading). Progressive lens blanks often have the distance portion decentered so that the near portion will be inset properly when you cut the lens. Typically, a PAL’s optical design is decentered inward by ~2.5 mm from the geometric center of the blank (this is sometimes called “blank inset”). This complicates blank calculations slightly, because if a design is pre-decentered, the lab might not need to decenter as much physically. But from a practical standpoint, the lab still positions the lens for the patient’s distance PD at the fitting cross, and the PAL’s internal inset takes care of near alignment. Just know that PAL blanks are not always optically centered in the middle of the blank – the “sweet spot” is shifted nasally a bit in the blank. This is yet another reason PAL blanks are larger: they built in room for that inset and near zone on the lens.

- Monocular PD and Heights: For progressives, opticians always use monocular PDs and the fitting height for each eye. So the MBS might differ for right and left as we noted. In a well-fitted symmetric frame it might be the same; in a frame where the patient’s eyes sit a bit off-center, one lens could need a slightly bigger blank. Labs will accommodate that accordingly. It’s not that single-vision doesn’t do this (monocular measurements are used for any high Rx), but with progressives it’s standard procedure.

- Frame Choice is Critical: With PALs, there’s an extra layer – the frame not only needs a certain lens blank size, but also sufficient vertical depth for the reading portion. If a frame is too small (low B measurement), even if the lens blank could be cut, the reading zone might be cut off – leading to a suboptimal progressive experience. So “minimum blank size” alone doesn’t guarantee a PAL will work; “minimum frame height” must be considered too. However, those are separate criteria. From the lens blank perspective, as long as the frame meets the PAL’s fitting height requirement, you then calculate MBS similarly and ensure blank availability.

In summary, single-vision vs progressive in terms of MBS calculation: the basic idea of ED + decentration applies to both, but progressives entail considering vertical placement and often use inherently larger blanks for their design. Many progressives come only in one or two large blank sizes, so often the lab just uses those. The challenge is more often “will the lens cut out without losing the reading area?” which is solved by proper frame selection and sometimes by the aforementioned charts or software. For an optician or optical enthusiast, it’s enough to know that the more complex the lens, the more you need to be sure about MBS. When in doubt, err on the side of a slightly bigger blank or consult the lens manufacturer’s recommendations. They design their lens blanks to accommodate typical needs, but extreme prescriptions or unusual frame shapes can still push limits.

Conclusion: MBS as the Unsung Hero of Great Glasses

The concept of Minimum Blank Size might seem technical, but it underpins a lot of what makes your glasses comfortable, attractive, and optically precise. It’s the reason your lenses fit just right in your funky new frames, and why they aren’t any thicker or heavier than they need to be. For optical professionals, MBS calculations are a daily routine – a blend of math and material savvy that ensures each pair of lenses is made from the optimal starting material. For consumers and the curious, it’s another insight into how a seemingly simple object (a pair of glasses) is actually a minor engineering feat: every millimeter counts!

Next time you pick out a new frame, remember there’s a behind-the-scenes puzzle to solve: Can lenses for your prescription be cut for this frame, and what lens blank will make it happen? A good optician has already done that math – possibly using a handy MBS calculator – to make sure you’ll get the best lenses possible. It’s one of those things you’ll never notice when done right (your lenses will fit perfectly), but you’d definitely notice if done wrong (imagine being told “sorry, your lens is too small for the frame” or ending up with periscope-thick lenses).

In the world of eyewear, precision is everything. Minimum blank size is a perfect example of that principle: a one or two-millimeter difference on paper can decide whether your new glasses are a success. By understanding MBS, you’ve gotten a glimpse into the craft of lensmaking. It’s a blend of optics, engineering, and even art – cutting a lens to fit a frame is like sculpting, and MBS is the size of the marble block you need to start with.

So, whether you’re an optical professional refining your craft or a curious eyewear aficionado, keep Minimum Blank Size in mind as the silent partner in every perfect pair of glasses. It’s the metric that ensures form meets function – that your lenses not only correct your vision, but also seamlessly become one with the frames you love, all through the magic of knowing the minimum size uncut.

I am a seasoned software engineer with over two decades of experience and a deep-rooted background in the optical industry, thanks to a family business. Driven by a passion for developing impactful software solutions, I pride myself on being a dedicated problem solver who strives to transform challenges into opportunities for innovation.